But everything wasn’t coming up roses. As with any worthwhile venture that is trying to change the world, there were challenges, and there were problems. The biggest challenge was keeping up the relentless growth expectations of our industry, as represented by the 30% month-over-month (MoM) growth target that GT insisted we hit if we were to remain a Venture Capital darling. For those of you playing the home game, 30% MoM is a great number to aspire to. But it’s also merciless. It’s grueling. And in the healthcare industry — where 10% MoM growth is normal and expected — 30% is nigh impossible. It’s suicide.

Better managed to average 17% MoM growth (even 20%-30% whenever we weren’t fundraising), annualized across the history of the company. A remarkable feat in our industry. But it was never enough. The bar was ever raising and regardless of the good we did in the world, the thing that mattered most was the hard data. Our growth numbers. Would we hit them? What would happen if we didn’t? When we didn’t?

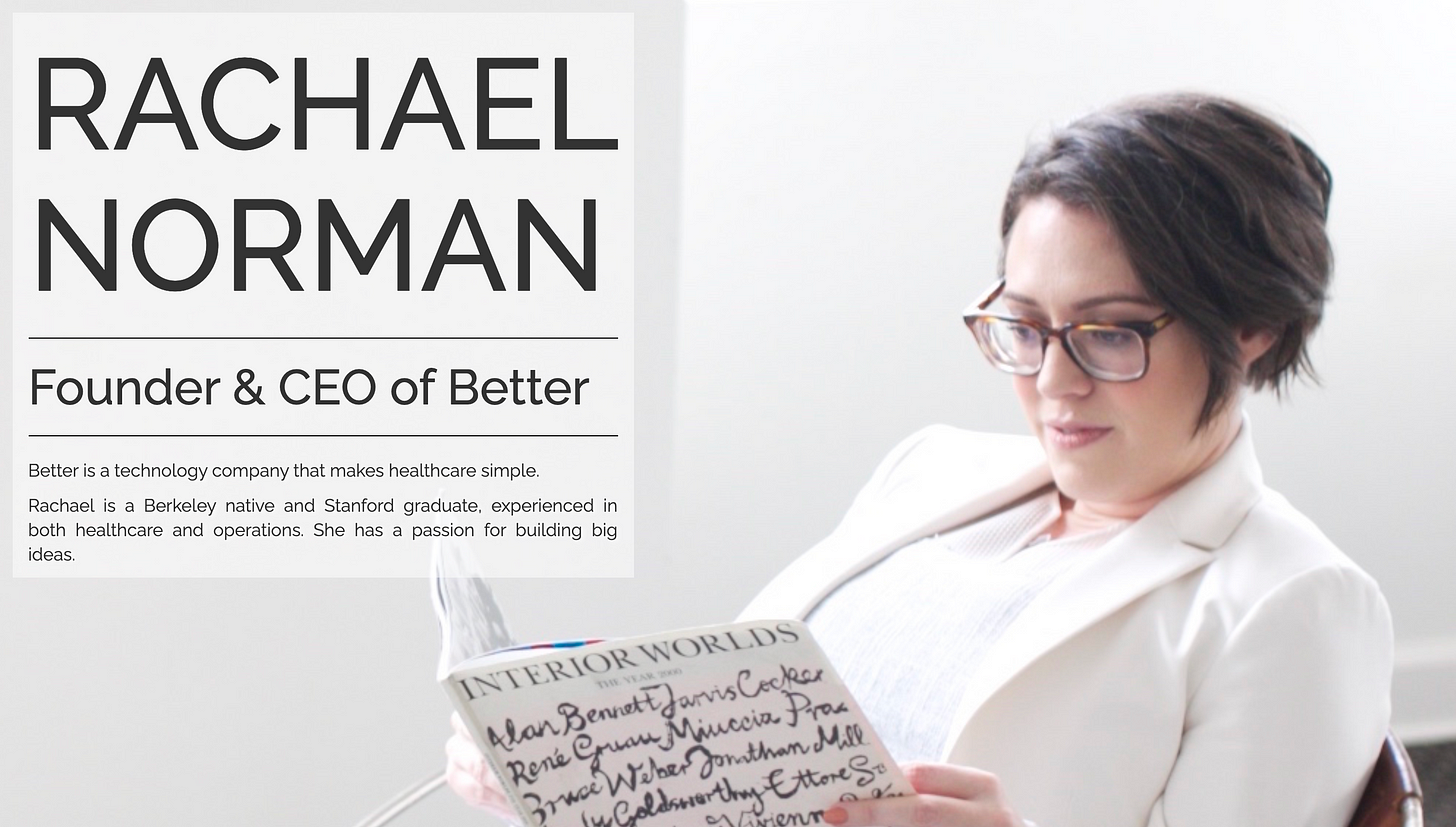

In January and February of 2018, Rachael ran one of the tightest and most efficient Series A processes I’ve ever seen in Silicon Valley. She kept meticulous spreadsheets. Parallelized outreach and timed all of the interest to coincide in a window spanning two weeks where our ~100 warm intros turned into ~10 closely vetted partner meetings. For the best startups, generally about 50% of partner meetings result in term sheets. We had verbal commitments for 5–8 term sheets from the top names in Silicon Valley. The unthinkable happened. Before we could even get all of the interested parties in the door, The Venture Fund sent over a blank term sheet, specifying 25% fully-diluted ownership of the company, and a blank dollar value. The implication?

“Name your price.”

In March of 2018 we signed a Series A term sheet with The Venture Fund. It was everything we had ever dreamed of… $9M on a $21M pre. The Venture Fund settled for 23.3% ownership for $7M invested. $1M each would be filled out by strategic funds and angel investor pro-rata. The sort of round founders talk about at the dinner table and share war stories with the hopes of closing.

Four days after we signed the deal, and one day after her birthday, we checked Rachael into a mental healthcare facility. The best money could buy. Rachael was suffering from anxiety and depression brought on by our relentless schedule and non-stop need to meet our next milestone. The need to push hard on our metrics overshadowed self-care, overshadowed our friendships, and overshadowed any hope of a happy ending.

A few weeks later when Rachael’s treatment wasn’t proving effective in Ohio, we facilitated her transfer to Bridges to Recovery. Bridges is one of the premier mental health and rehab facilities in the country. Patients stay in luxury accommodation in Beverly Hills and no expense is spared in their treatment or care. As with the entire mental health and rehab industry, there is plenty of criticism to be placed in how these facilities operate. They charge exorbitant fees that are outside the means of most individuals, promising levels of care that whether realized or not, may be insufficient to deal with the problems their patients face. I personally sent Bridges nearly $60k and Rachael was admitted. We would spare no expense in order for her to get better.

As soon as you sign a term sheet, two things happen. First, “The Company and its employees and officers shall not initiate, solicit, encourage, discuss, negotiate, or accept any offers for the purchase or acquisition of any securities of the Company (other than Preferred Stock contemplated by this Term Sheet), or all or substantially all of its assets for 30 days following execution of this Term Sheet.” Which is a fancy way of saying the dating game is over. Other options are now off the table for finding funding. Secondly, diligence begins. Which is a fancy way of saying The Venture Fund wanted all of the records pertinent to our business so they could very carefully have their people inspect the fastidiousness of our HR practices, accounting, cap table, and other relevant business practices.

Despite understanding I was working hard to procure countless documents for legal diligence. Back in San Francisco, The Venture Fund was getting impatient. They didn’t know why we had gone radio silent after signing a very lucrative term sheet that both The Venture Fund and all of us at Better were very excited about. I was determined to represent the facts of our situation honestly and accurately, but I also was petrified. I had enough experience in Silicon Valley to know that VCs invest in CEOs and in founding teams. If Rachael wasn’t going to be operational soon, the deal could be off. And for better or worse, the only choice I saw at my disposal was to buy some time.

I put off our meetings with The Venture Fund for the time being, and tried to focus on Rachael’s care plan while running Better single-handedly. It was hard. No, strike that. It was impossible. But we all tried. Our entire team banded together and pushed hard to keep the gears turning and be ready to hit the ground running as soon as Rachael’s course of treatment was finished. There would be challenges, but we would get through this test.

A few weeks later we had a meeting on the books with The Venture Fund in order to talk about something or other with their people-person. The one you go to when you need a COO or other leadership role. I forgot it was scheduled and was not only unprepared for the meeting, but didn’t have a good answer for why Rachael wasn’t present. The Venture Fund was spooked and didn’t know what to do. Our partner on the deal and I set up a meeting to talk through the entire situation.

As with all sufficiently interesting Silicon Valley stories, this too finds us at the Creamery in SoMa (farewell). Our partner at The Venture Fund arrived on a Jump bike — as usual since they had been instrumental in funding Uber’s Series B — and we dug in. I shared everything that had happened and we hashed through possible paths forward. This was an extraordinary circumstance and everyone expressed a desire to be sympathetic and supportive. In this meeting and subsequent discussions over the next days and week, we worked through possible strategies to fund Better and mitigate any associated risks for The Venture Fund. We had a plan. Almost.

The Venture Fund decided that the risks introduced by my co-founder and CEO’s hospitalization were significant and needed to be mitigated, but were not toxic. They could still proceed with the deal, with some minor modifications. We discussed tranching the round, with $3.5M coming up front, and establishing milestones for Better receiving the balance of the funds upon proving performance with me at the helm. We were back in business.

Although Rachael was still finishing up care at Bridges — the same facility that Britney Spears would seek treatment a year later — she was available for calls and still calling the shots. I got on the phone with her and got Rachael up to date on the new plan. And she hated it. How had I lost over half the round? Why would we accept a tranched deal? We had ~5 funds in play ready to write us a term sheet… Rachael demanded to know how I had fucked this up so badly.

In order to triage the situation, Rachael and The Venture Fund got on the phone. Rachael demanded the full deal. We were worth it. This was a rocketship to the moon and The Venture Fund knew it. The Venture Fund agreed that other options were on the table but if they were to be discussed, Rachael would need to be there. Rachael and The Venture Fund arranged a meeting the day after she was to be discharged from Bridges. Rachael would come back and instill faith in the faithless.

But it was not to be. The meeting around May 24th of 2018 with The Venture Fund was a catastrophe. Our partner at The Venture Fund had brought along an analyst or associate. The analyst demanded to know why we had missed our growth numbers over the past two months, while Rachael was in treatment and the company had exhausted our runway. They poked and prodded. They claimed that our projected numbers — that were predicated upon receiving $9M of funding in March and being able to open our growth floodgates — were the most deceptive representation of a company that they had ever seen. They negged Rachael, myself, and our team. They demanded a second round of diligence with entirely new up-to-date data. It was our worst meeting ever.

Rachael, myself, and Anton (Rachael’s boyfriend) doubled down. We produced volumes of data. We shifted all of our analysis over to Jupyter, a python data-analysis platform that enabled us to have always-up-to-date reports on the state of the company. We exhaustively poured over and over the numbers. We found minor errors or inconsistencies, and threw out our methodologies repeatedly. Eventually we were satisfied with our data and stamped it as gold-standard. This was going to save the deal. We sent the data to The Venture Fund. And The Venture Fund pulled out.

At any other startup, that would have been the end. A founder dealing with health issues due to overwork. One of the best venture deals of the year negotiated. And everything falling apart. But Better was different. Without the support of The Venture Fund and the $7M (of $9M) they had promised to provide, Better was running out of funds. And fast. We woke up one day in June and the writing was on the wall. We were out of time.

Our bank account was in the red. The company wasn’t to the point of bringing in revenue yet (despite our very promising growth), and as such the only way out would be a lifeline from one of our supporters. Very few stories from the Valley continue past this point. Not many founders or teams can get out of such a predicament. But Rachael was never deterred. She texted one of our strongest and most loyal supporters, Lee Linden. And the next day, $600k appeared in our bank account.

The next few days felt like a movie. Our team was united. We had a new lifeline on life. We had literally been saved by the miracle from Lee. No one knows what Quiet does. But they had previously tendered us a LOI for $1M. And even in the worst of times, they came through and put their money where their mouth was: Quiet Capital may have been the most unknown stealth fund we talked to, but they were the most crucial and supportive to the success of our journey. Lee saved Better. And we would do him and his whole team proud.

Around this time in the story, cracks were starting to form in our team. We had started the company on a shoestring budget and everyone that had come along on the journey sacrificed with us. Our team was making $60k-$120k in a market where less-mission-driven employees were being paid $100k-$250k. Our team was underpaid, overly-passionate, and exhausted. And they had put everything into making it to our Series A. That was our light at the end of the tunnel. The pot-of-gold at the end of our rainbow.

Some of our team reached their breaking point. They demanded explanations. “Why has Rachael been allowed to step away from her responsibilities in order to seek care?” “Shouldn’t someone else be running the company?” “Shouldn’t you be running the company, John?”

I was firm. This was Rachael’s company. Her baby. She had envisioned Better’s entire existence through her own experiences of not being paid back by her insurance for care. She deserved our support. We would get through this. I rallied the team and sounded the battle call. But not all of our team was satisfied.

One of our employees at the time quit in protest. They had been incredibly passionate about our mission. But they were also struggling financially and our Series A falling through was the last straw. The employee quit. Common decency demands that this be the extent of an employee’s damage to an employer. If you don’t agree with the team or vision you are being paid to execute, leave. Just don’t torpedo the ship.

This employee went further. They posted a scathing takedown of Rachael on Glassdoor. They encouraged other ex-employees to do the same. And though we thought that was petty, and awful, and sad,… we kept persevering.

Rachael would spend the next — and last — year of her life cursing these Glassdoor reviews. Around the same time they showed up, something changed in our relationship with our lead investors. The Seed Fund — one of the most aggressive and successful firms in SF — got cold feet. We got shifted around and then passed off from the partner to a fresh young face: AL. Rachael always hated AL. She felt like, from day one, AL was out to get her. GT was always kind and engaged, but Rachael felt like AL couldn’t stop negging her. It was always a new problem with AL. And we made the conclusion that he was a fixer sent to gradually terminate The Seed Fund’s support of Better.

The rest of the story is increasingly sad, tragic, and heartbreaking. Rachael and I continued in good faith to persevere. To raise funds. To try to save our company. We didn’t understand why The Seed Fund’s excitement had faded. We had been one of their investment darlings … “Top 3% of our portfolio.” GT had always loved us. But now we were on the outs.

Better was an incredible company. Fighting the good fight. Our investor and friend Alexis Ohanian praised us for being everything right in Silicon Valley. Speaking at the Milken Institute Alexis said of Better–

“There’s a shift that is happening, and so I would not throw out the whole Silicon Valley baby with the bathwater, because there are some really amazing founders that are working on great stuff. […]

If you have a true purpose and a true reason for people to want to wake up and work, that’s a competitive advantage.”

–Alexis Ohanian on Better

We had every advantage. But we also had a crucial flaw. We were unwilling or unable to give up. We believed so much in our purpose and in the good that we were doing in the world, that failure was not an option. Running out of money? John would pay payroll out of savings. We’d spend all day every day fundraising. We’d squeak it out and we’d close a new Series A. Some days the plan worked. Rachael and I were laser focused and we would succeed. $25k here. $5k there. Every bit of investment counted. We were excruciatingly clear about our tenuous situation with everyone. But enough people believed to keep Better afloat. My old friend Bobby agreed to lifeline us $100k. One of our new venture capital friends agreed to a $150k investment during a 27 minute call. We were still reeling in miracles. But just barely in time.

Despite our successes in fundraising, one of the most confusing patterns was how many potential investors fell off or ceased being interested very late in the game. It had become normal for investors that were ready to write checks to speak with The Seed Fund and come back trepidatious. They would ask why The Seed Fund wasn’t leading our next round. Why there wasn’t more confidence. They implied that the company had lost the faith of our strongest supporters. Why?

The final piece to this story is also the most tragic. During the last months of Better’s operation, Rachael was increasingly alone. Despite my always being there to check in or take care of her — and I had become one of her only close friends and her sole caretaker after her boyfriend threw in the towel — I couldn’t be there always. And Rachael was proud. She hid the core of her struggles from me. And when her world-class psychiatrists and care team failed in resolving her anxiety and depression, she resorted to dealing with them herself. “Heroin is one of the best anti-anxiety drugs on the planet. That’s what one of my psychiatrists told me.”

July 9th, 2019, was a mostly-ordinary day. Rachael and I worked together. We dealt with an intransigent email from a self-entitled contractor that quit with fanfare — sending a cutting email that bullied and demeaned Rachael in particular — and we got through our day. Around 6:30pm or 7pm Rachael finished a discussion with one of our other employees and went home. I went over to her apartment an hour and a half after she left work. I had finished up my own work at our office at 580 Howard Street, and taken a car to her house a few blocks away in SoMa.

Rachael lived in a loft in SoMa, with a small guest room underneath the main living space. A single PIN-protected door opened onto the street. I coded in a now-forever-lost PIN from my barely functioning and exhausted memory, and I entered. And my entire world shattered. The apartment was too quiet. “Rachael?” … “Honey?” … *silence*

I rushed upstairs with anxiety and concern. Something was wrong. Was Rachael here? Was Rachael gone? Nearly at the top of the bedroom landing stairs I saw her. Lying on her bed. Airpods playing Taylor Swift. Not breathing. She was turning blue in the face. God knows I didn’t know how long she had been down. I didn’t waste a second. I pulled Rachael off the bed, Airpods tumbling out of her ears, and I started CPR. I put my phone on the bedside table and called 911 while I fumbled through my bag looking for the nasal Narcan I had constantly carried for the last two weeks. Ever since Rachael had mentioned the possibility of opioid abuse. Four and a half minutes later the paramedics arrived.

The paramedics, nurses, doctors, and balance of Rachael’s care staff would later tell me that I did everything right. That as I stood there, shaking, praying, begging the universe to save my friend, and telling her that I loved her. That I would always love her. It was already too late. Despite having CPR training from my PADI Rescue Diver course and despite not wasting a single moment. Despite having Narcan with me. Despite everything, it was too late.

Rachael was admitted to the ICU at SF General Hospital and remained in a coma for the next 9 days. Her prognosis never improved. Rachael never woke up. On July 18th, 2019, Rachael Norman was removed from life support and passed away surrounded by a small group of friends she loved as her family.

After Rachael passed away, I immediately went into meetings with The Seed Fund. For the most part, they were sympathetic. I had just lost my co-founder and I was empowered. I demanded they bridge our team and keep Rachael’s vision alive. We had proved the value of the space. We had a working product. We just needed the money that never came from The Venture Fund. We needed a Series A. I thought my ask was reasonable and the situation extraordinary. I was certain this would work. But the responses I received constantly revolved around The Seed Fund’s preoccupation with “data irregularities,” “bad data,” and our claims database. They were convinced something was askew. Could their demands of 30% growth have caused the company to stretch the truth??? They dug for a truth that didn’t exist. I was confused.

Steve Jobs once said that “Death is very likely the single best invention of life. It is life’s change agent.” Clearly Steve Jobs never dealt with untimely death. I spent the next month taking meetings with One Medical, and 4 other acquisition or acqu-hire partners. I took an all-for-one and one-for-all approach. Any interested acquiring partners would have to take the whole team or none of us. No poaching engineers. Taking the technology or IP was optional. At the end of the day lots of our discussions were promising. But nothing made it over the finish line. Eerily like fundraising before, the acquisition partners fell off like flies after speaking with The Seed Fund. What could have caused our lead investors to so lose faith in our mission?

Better failed to find a home and ceased operations August 15th of 2019.

Nearly a year and a half after my co-founder, burning man camp co-lead, and best friend died, one thing is clear: I still have yet to place together all the pieces of this puzzle. What do I know for certain? Better was a company that tried to change the world, and failed. We didn’t have the confidence or support of our community when we needed it most. We didn’t have a big red button we needed to push when the going went from difficult to impossible. At the end of the day, Silicon Valley is excellent at encouraging founders to take immense risks in the name of changing the word, but we are terrible at supporting the same founders through their successes and failures. We enable a perverse meritocracy where those that succeed are those that are left standing. This must change.

Building Better with Rachael was the most meaningful experience of my life; losing Rachael was the most difficult experience of my life. The world lost one of our brightest lights. It doesn’t need to be this way. We can do better. We can give better tools to founders. We can better support early-stage companies and teams with support networks. We can build tools to help on the bad days, not just the good. There should be better ways to escalate and triage difficulties. There should be a Big Red Button that founders can press when it all becomes too much. It takes a village. We must do Better.

If you’d like to read more about Rachael Norman and her journey, you can find much of her original writing at http://rachaelnorman.com

We love you Rachael! Godspeed.